Blog #5: The innate immune system (The start of an amazing journey) (Lay Version)

- louiscatania

- Apr 28, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 8, 2023

(Selected Tables and Figures referenced, but not present in this blog

can be found in their corresponding Science Version blogs)

It’s simple! Immunity is our body’s battle of “self-versus-non-self.” The ability of your body, which we’ll call “self,” to resist things like bugs or infection and irritating substances in the air like dust, mold, or even toxic substances like smoke and pollutants. We’ll call these external irritants “non-self” or foreign matter, or the scientific term for them, “antigens.” Your body is constantly fighting off these foreign, “non-self” substances by using specialized molecules in your body and in your blood called “immune cells,” certain kinds of white blood cells called “lymphocytes” and molecules called “antibodies.” These blood cells and molecules are part of your immune system and their actions to protect us and eliminate the bad guys are called our immune response or immunity. As part of the complexity of our immune system, there are an abundance of mysteries and contradictions that the book, "The Paradox of the Immune System," identifies and “tries” to explain. The “self-versus-non-self,” battle described above represents perhaps the most prominent paradox of the immune system. It also sets the stage that explains how the system works to protect us 24/7. The system functions as a natural process in our body and we call this natural, normal immune process “innate immunity.” But sometimes our innate immunity is insufficient to overcome those antigens we’ve described and it has to “adapt” itself to function in a tougher and more specialized way. This more aggressive level is called “adaptive immunity.” Blog #9 will address the specialized ways, called the molecular biology, of how adaptive immunity works to protect us. But first, we want to understand how innate immunity works to protect us under normal circumstances and what happens when it can’t complete the job.

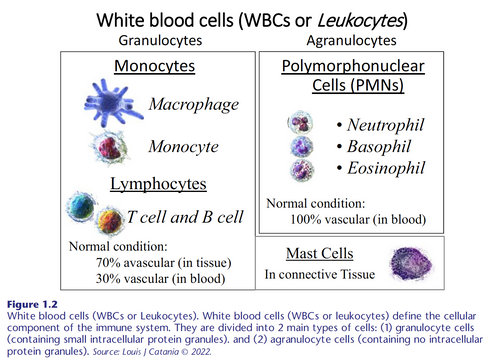

Certain organs in our body (Figure 1.1) produce those white blood cells (WBCs) or lymphocytes we mentioned above. There are numerous organs that produce these immune cells (Figure 1.2), but most of them come from the thymus gland in the upper center of our chest and from the inner core of our bones called the marrow. The WBCs include the now famous T and B lymphocytes and some other cells that assist in the protective immune functions. And start thinking big here because we’re talking about trillions (with a T) of these immune cells. The innate system also uses some of the body’s gross anatomical structures, especially the skin and mucous membranes as protection against attacking antigens. So, as you are reading this blog or

listening to this podcast, you are being constantly attacked by countless foreign antigens including dust, pollen, spores, virtually anything airborne or touching you. Your T “helper” cells are going to work to recognize those antigens and activating your innate immune response. To do this, certain programmed genes developed over eons of evolution recognize the antigen and determine its level of threat and if the Th cells should “attack or stand down.” If the foreign substance presents a danger to the body, the Th cells are directed by chemical signals to attach themselves to surface proteins on other immune cells and together, bind and disable the antigen molecules (Figure 1.3). This amazing system of “antigen recognition” protects us from overworking our immune system and more so, protects us, “most of the time” from attacks on our own body. This starts the intimate relationship between our immune system and our genes, a relationship that will direct and control the immune system going forward. The chemical signals and proteins generated in this exquisite natural process of innate immunity also stimulate other specialized T cells called T regulatory cells (Treg ) and another category of lymphocyte cells called B cells. These critically important B cells will begin to produce antibodies, the molecules that will also recognize the attacking antigen through their own specialized genes and will assist the Th cells in binding remaining antigens or antigens that might be resisting or escaping the Th cell attack. This overall immune process is called the “regulated” innate immune response. And the functions already described, the T and B cells will begin to generate memory cells to protect our bodies against any future attacks and reinfection by similar antigens. In some instances, albeit rare relative to the trillions of antigens our body is constantly defending against, the antigen load may prove to be too great, too strong, not being removed quickly enough, or the immune system itself is suppressed for some reason (called “immunosuppression”). In these cases, the innate immune system keeps fighting harder but is also creating an abnormmal, increasing accumulation of cells and chemicals in our tissues that can begin to be interpreted as “foreign” and producing “stress” and disruption of the normal physiological balance (remember homeostasis?) our body is used to. All this can lead to a “dysregulated” immune system where confusion (or paradox) develops as to “who are the good guys and who are the bad guys?” This dysregulated system now begins to interpret “too much self” as a “foreign stimulus.” It starts to generate an increasing cell and chemical response or an “overreaction response” as part of its protective function. This is when the innate immune system begins to “adapt” into a the more aggressive “adaptive immune system.” This is the system that the body will now use to deal with accumulated debri, its increasing stress on the body, and the new risk of reacting to itself, or “autoantigenicity.” The first event this adaptive immune system will initiate in mounting its defense is a classic clinical process called “acute inflammation.” We will be describing that in detail in Blog #9, “The adaptive (aka “acquired”) immune system: from friend to foe.”

Comments